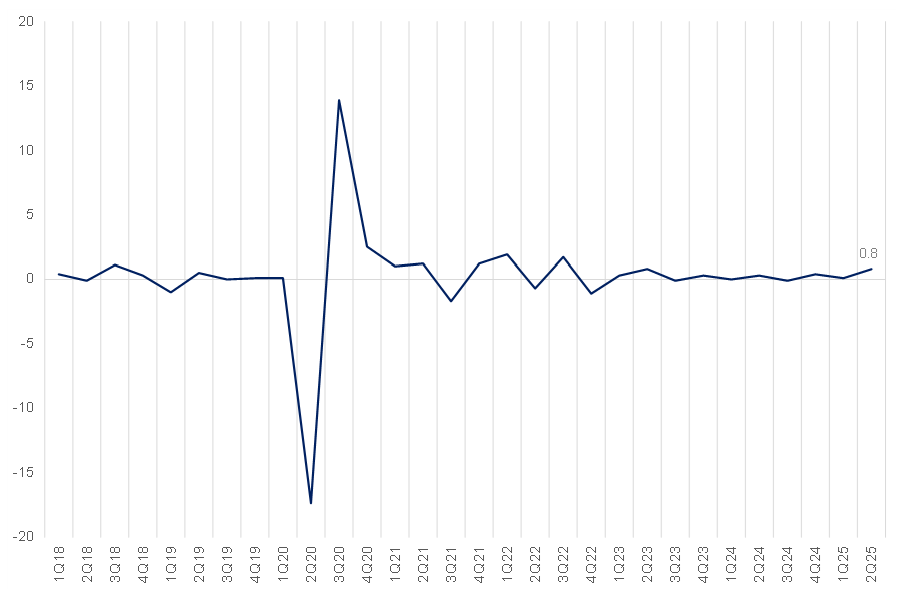

After just managing to stay afloat with growth of only 0.1% QoQ in 1Q25, South Africa’s (SA) real gross domestic product (GDP) showed a more convincing rebound in 2Q25, expanding by 0.8% QoQ between April and June. On the production side of the economy, manufacturing, mining, and trade were the main drivers, each contributing 0.2 ppts to the headline growth figure. The expenditure side of the economy also surprised positively, lifted by stronger household consumption and a moderation in imports.

Encouragingly, this outcome exceeded even the more bullish market forecasts, suggesting that domestic demand and supply-side activity were more resilient than initially anticipated. However, it is important to keep in mind that this latest data release reflects activity before the implementation of the Trump administration’s 30% tariff hikes on SA imports to the US, which came into force on 7 August. The timing matters: while the 2Q25 data offer a snapshot of an economy finding its feet, the impact of these higher trade barriers (particularly on the automotive sector and related manufacturing industries) is only beginning to filter through. Market expectations point to the brunt of these costs being visible in subsequent GDP prints, potentially complicating the growth outlook for the remainder of the year.

Figure 1: SA GDP growth QoQ % change

Source: Stats SA, Anchor

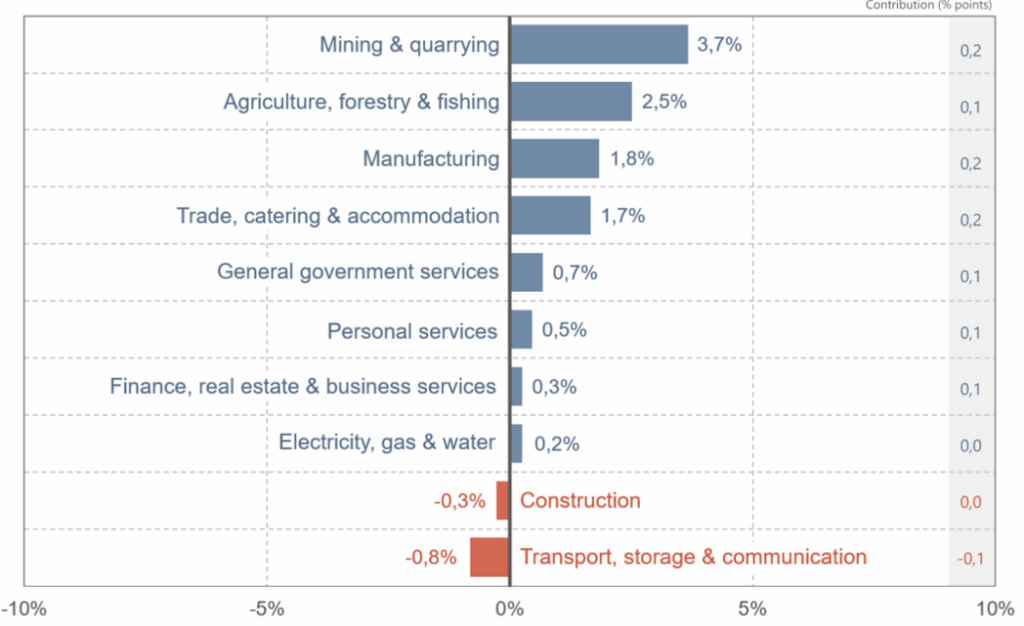

On the supply side of the economy, 2Q25 brought a welcome turnaround in key productive industries. After two consecutive quarters of contraction, both manufacturing and mining returned to growth. Manufacturing output expanded by 1.8%, buoyed in particular by the automotive sector – a bellwether for industrial momentum- alongside petroleum, chemicals, rubber, and plastics. Mining delivered an even stronger performance, rising by 3.7%, the fastest pace since early 2021. Platinum group metals (PGMs), gold, and chromium ore were the main drivers, underscoring the sector’s continued dependence on global commodity demand and pricing. Together, these gains signal that SA’s core industrial engines have regained some footing, offering relief in an economy where production-side weakness has been a persistent drag.

Consumer-facing industries also posted an encouraging showing. The trade, catering, and accommodation industry expanded by 1.7% QoQ, its best performance in over three years. Retail trade, motor trade, accommodation, and food and beverage services all advanced, suggesting households were willing to spend more despite cost-of-living pressures. Wholesale trade was the outlier, recording a dip, which may reflect lingering supply-chain bottlenecks or subdued business-to-business demand. Still, the broader resilience of consumer activity points to some stabilisation in domestic demand, an important offset in an otherwise challenging environment.

Agriculture extended its positive run, growing 2.5% in 2Q25 after a sharply revised 18.6% QoQ surge in 1Q25. Although growth slowed from the extraordinary pace earlier in the year, the sector continued to punch above its weight. The horticulture and animal products sub-sectors were the main contributors. Still, challenges persisted: outbreaks of foot-and-mouth disease, delayed vaccine rollouts, and a lagged summer grain harvest dampened momentum. These factors suggest that some of the output initially expected in 2Q25 may spill into 3Q25, providing potential upside in the next GDP print. Significantly, while agriculture is a relatively small share of the economy, the volatility in its quarterly performance has amplified its role in shaping headline growth dynamics. By contrast, construction and transport remained weak spots in the economy. Construction recorded its third consecutive quarterly decline, weighed down by ongoing softness in residential and non-residential building activity. Although construction works provided some offset, they were insufficient to pull the sector into positive territory. This underscores the structural challenges facing an industry long seen as a barometer for fixed investment and broader confidence. Transport, storage, and communication also detracted from growth, with land transport and related support services underperforming. Given the centrality of logistics and freight to SA’s trade performance, the sector’s weakness is a reminder of the drag that infrastructure bottlenecks continue to impose on the economy.

Figure 2: Industry growth rates, 2Q25

Source: Stats SA

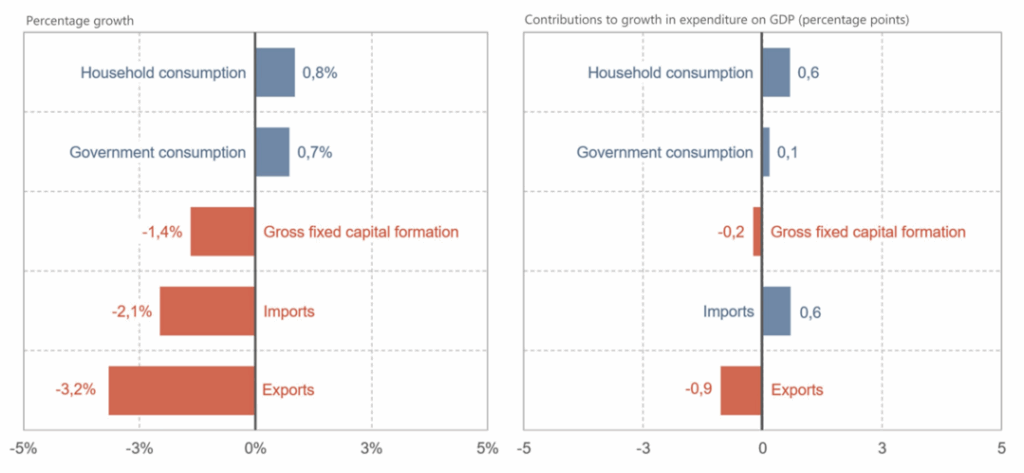

On the expenditure side of the economy (more commonly referred to as the demand side), the picture was mixed, with household consumption and a decline in imports providing the main positive contributions to growth. By contrast, gross fixed capital formation (GFCF) and exports detracted from overall momentum, underscoring lingering vulnerabilities in investment and external demand.

Household consumption rose for a fifth consecutive quarter, increasing by 0.8%. The miscellaneous goods and services category was the strongest driver, lifted mainly by higher insurance spending – an interesting development that may reflect households prioritising financial protection in an uncertain environment. Consumers also channelled more spending into restaurants and hotels, as well as clothing and footwear, suggesting that discretionary activity has remained relatively resilient despite persistent cost-of-living pressures. On the downside, households cut back on alcohol, tobacco, and narcotics, while also reducing demand for housing-related utilities such as water, electricity, and gas. This divergence hints at the balancing act consumers are performing, preserving lifestyle and leisure spending in some areas while tightening their belts in others.

After five consecutive quarters of inventory rundown, the economy finally recorded a build-up in 2Q25, amounting to R16.6bn. The rise was concentrated in mining and quarrying, transport and storage, and manufacturing. While positive for headline growth, inventory accumulation can be a double-edged sword: it may reflect firms gearing up for anticipated demand, but it could equally signal that goods are piling up faster than they can be absorbed by the market, potentially curbing production in later quarters.

Trade flows were less encouraging. Imports fell by 2.1% QoQ, driven by weaker demand for chemical products, machinery and electrical equipment, mineral products, and vegetable products. Although lower imports can mechanically boost GDP, the details suggest underlying weakness in productive capacity, particularly as reduced imports of machinery and equipment point to a softer investment appetite. Exports also declined, weighed down by reduced shipments of base metals, vegetable products, and vehicles (excluding large aircraft). This dual weakness in imports and exports highlights the economy’s external vulnerability: SA is not fully benefitting from global trade momentum, while at the same time failing to channel foreign-sourced capital goods into productive investment.

GFCF remained under pressure, extending the weakness already evident in 1Q25. Private investment fell by another 1.4% QoQ, reinforcing the picture of subdued business confidence and risk aversion among firms. This persistence of low investment, despite some expectations for improvement, is especially concerning for longer-term growth prospects. Without stronger momentum in capital formation (particularly in productive sectors like energy, logistics, and manufacturing), the economy risks becoming increasingly reliant on household consumption as the primary driver of demand.

Taken together, the 2Q25 expenditure figures highlight an economy still caught in a delicate balance. On the one hand, households continue to spend, and inventories are being rebuilt, providing near-term support. On the other hand, weak investment and declining exports point to structural constraints that will weigh more heavily in the medium term, especially as tariff-related shocks begin to filter into trade and production.

Figure 3: QoQ % change in expenditure components and contributions to expenditure on GDP

Source: Stats SA

The stronger-than-expected rebound in 2Q25 offers some relief after a sluggish start to the year. However, it does not fundamentally alter the broader picture of an economy still struggling to build durable momentum. Early 3Q25 indicators, from the Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) surveys to business confidence, point to a fragile recovery at best. While manufacturing activity may gain modestly, structural headwinds such as automotive production stoppages, the closure of key steel operations, and persistent weakness in export demand could temper any gains. Business confidence, already subdued, slipped further in 3Q25, with only 39% of firms reporting satisfaction with prevailing conditions. This level of sentiment is consistent with an economy “muddling through” at around 1% growth, far below what is needed to generate meaningful job creation or income growth.

For the average South African, the implications are sobering. Household consumption has held up, but mainly through spending shifts and greater reliance on categories like insurance and discretionary services, rather than a surge in incomes. Employment creation remains weak, wages are under pressure, and the cost of living continues to bite with tariffs, administered prices, and food inflation set to weigh further on household budgets in the coming months. The persistent weakness in private investment also matters. Without businesses committing to new factories, logistics upgrades, or energy projects, job opportunities remain constrained, leaving households without the income security needed to sustain stronger domestic demand.

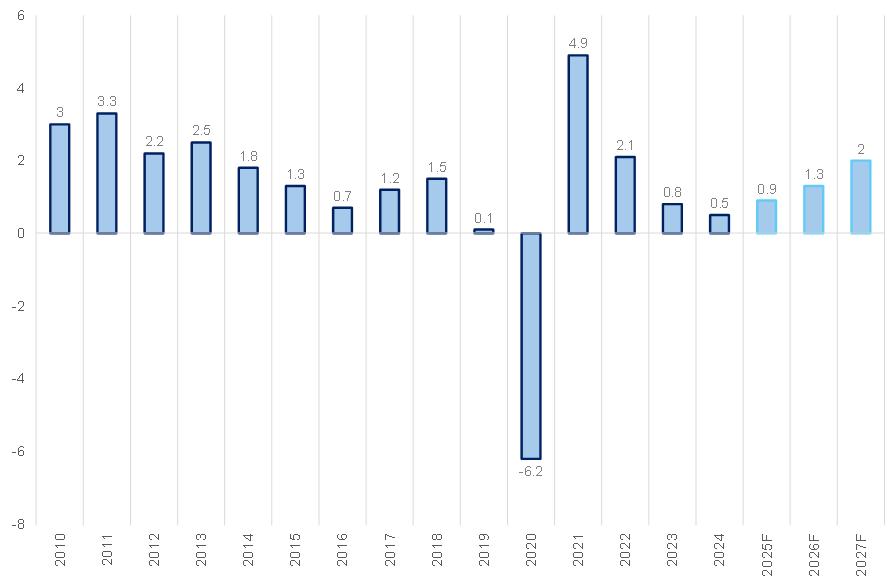

Figure 4: SA GDP annual growth rate, YoY % change

Source: Stats SA, SARB, Anchor

The official outlook has accordingly tempered. The South African Reserve Bank (SARB) has cut its GDP growth forecast for 2025 to just 0.9% (from 1.7% at the beginning of the year), while the IMF projects a similar 1% pace. Even looking further out, growth is expected to remain modest at 1.3% in 2026 and 2% in 2027 – levels that are insufficient to meaningfully improve living standards. Political uncertainty within the Government of National Unity (GNU), slow progress on structural reforms, and continued inefficiencies in logistics and energy supply further erode both business and investor confidence.

In short, the 2Q25 GDP rebound is a welcome signal that parts of the economy (notably mining, manufacturing, trade, and agriculture) still have the capacity to surprise on the upside. Nonetheless, for South Africans on the ground, the reality is that growth remains too low, too narrow, and too fragile to meaningfully ease unemployment, reduce inequality, or lift real household incomes. Without decisive reforms to unlock investment and rebuild confidence, the economy risks remaining stuck in a low-growth trap, where even small gains feel elusive against the weight of structural constraints and everyday cost pressures.