South Africa’s (SA) monetary policy framework is at a critical juncture. For the past 25 years, the South African Reserve Bank (SARB) has operated under an inflation-targeting regime, aiming to keep price growth within a 3%–6% band. Since 2017, the Bank has increasingly emphasised the 4.5% midpoint, successfully shifting expectations downward from the upper end of the target range without sacrificing growth. However, in May 2025, SARB Governor Lesetja Kganyago and the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) took a bold step: Publishing a scenario based on a 3% inflation target and calling it “more attractive” than the status quo. This was more than a technical exercise—it was a signal that the central bank now views 3% as the desirable anchor for SA’s future.

The debate that followed has been vigorous, cutting across financial markets, academia, and politics. Advocates see alignment with global norms, fiscal gains, and lower interest rates. Critics warn of growth sacrifices, sticky administered prices, and political discord that could undermine credibility. The road to a 3% target, in other words, is not merely a technocratic adjustment- it has a far-reaching impact across SA’s greater macroeconomic policy framework.

The case for a 3% target

Proponents of lowering the target argue that SA is an outlier. Most emerging markets (EMs) have already narrowed their ranges or moved to point targets around 3%, while developed-economy trading partners operate even lower. Maintaining a higher target imposes costs: It embeds a risk premium into borrowing, keeps interest rates structurally higher, and erodes competitiveness.

SARB modelling suggests the benefits could be substantial. The MPC’s latest analysis, released in July 2025, presents a scenario where lowering the target to 3% allows the repo rate to be 50 bpts lower in 2025 and up to 150 bpts less in the longer term. Such a shift could gradually bring borrowing rates below 6%, rather than keeping them stuck above 7%. Lower inflation would not only make credit cheaper for households and businesses but also reduce government debt-service costs, potentially saving the fiscus R130bn in five years and up to R600bn by decade’s end. By lowering the inflation risk premium, borrowing costs on new debt issuance would steadily fall, providing much-needed fiscal space at a time when SA faces heavy refinancing pressures.

The consumer and business benefits are equally important. A lower inflation rate would shield households, notably lower-income ones, from food and fuel price volatility. At the same time, businesses gain from cheaper capital, stronger investment planning, and potentially higher job creation. Moreover, the Bank’s credibility, strengthened over years of consistent policy, suggests that transition costs could be minimal. Headline inflation has already fallen below 3% in recent months, offering a rare window to anchor expectations at a lower level. Governor Kganyago has made the logic explicit: “A lower target will lock in lower interest rates going forward. SA would be a lower-inflation, lower-interest rate economy.” The lesson is simple: Low inflation is the price of sustainably low interest rates.

The risks and reservations

Despite the apparent gains, questions remain over whether the SARB’s modelling reflects the most likely transition path or an idealised best-case scenario. The Bank assumes inflation expectations will quickly re-anchor to the new 3% level, but others are less convinced. Codera Analytics, in a February 2025 paper, argued that domestic inflation expectations remain highly backwards-looking. Without structural reforms and government buy-in, promising a lower target could backfire- the tradeable sector would be forced to undershoot dramatically to offset sticky administered prices, and the private sector would bear disproportionate adjustment costs.

Concerns have also been raised that the SARB’s assumptions rely on a supportive fiscal environment, including debt-service cost projections that differ significantly from those in the Treasury’s Budget 3.0. If fiscal consolidation falters, lower borrowing costs may not materialise, and instead the central bank could be left maintaining higher nominal rates than under the current 4.5% target. In this sense, the SARB’s analysis shows what is possible, not necessarily what is probable.

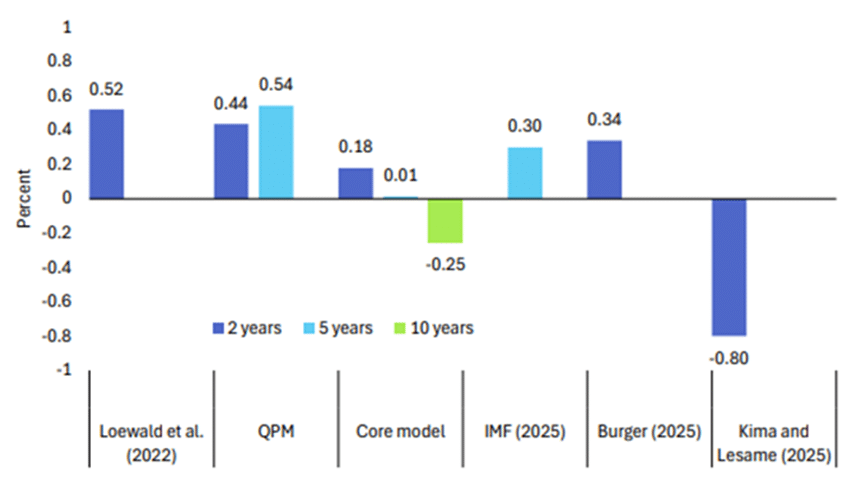

This uncertainty is reflected in estimates of the “sacrifice ratio”- the extent to which lowering inflation requires giving up output. Figure 1 below illustrates the wide range of estimates across models and institutions.

Figure 1: Comparison of sacrifice ratio estimates

Source: Codera Analytics

The SARB’s internal modelling suggests that the sacrifice ratio could be close to zero over the medium term, implying minimal output loss. However, other estimates vary dramatically, from small positive costs (0.3%–0.5% of GDP) to more optimistic scenarios where long-run gains outweigh initial sacrifices, to deeply negative short-term shocks such as the 0.8% contraction projected by Kima and Lesame (2025; in a working paper by UNU-WIDER and Treasury which models how a 1-ppt reduction in the inflation target could affect the broader SA economy.) This divergence highlights the uncertainty surrounding transition dynamics. As Codera so aptly stated in a recent blog post, “there are as many sacrifice ratio estimates as there are economists.”

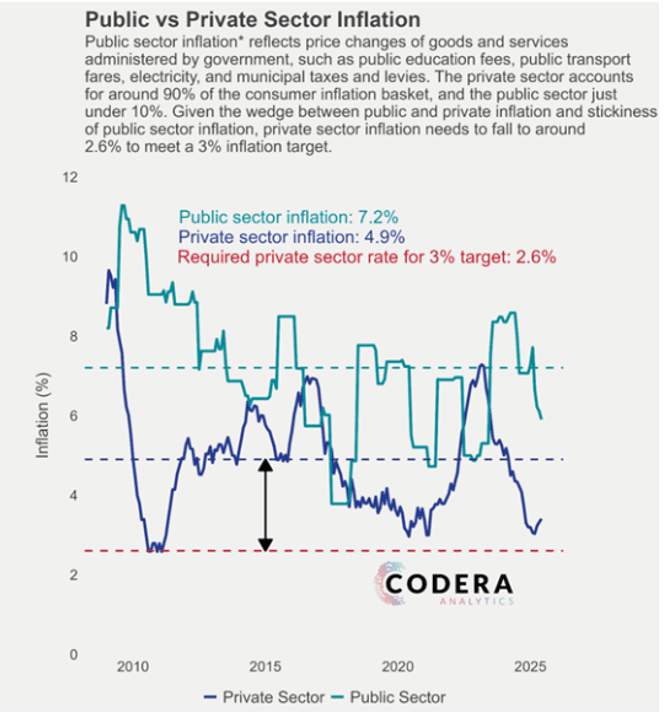

Structural obstacles compound the challenge. A significant share of SA inflation stems from administered prices (i.e. electricity tariffs, municipal charges, public sector wages) that consistently rise above headline CPI. Unless these are brought into line, the burden of achieving 3% would fall disproportionately on the private sector through higher interest rates.

As the graph below from Codera illustrates, since 2009, public sector inflation (driven by administered prices such as education fees, municipal rates, and electricity tariffs) has averaged 7.2%. By contrast, private sector inflation has averaged 4.9% over the same period (excluding fuel). If SA were to pursue a 3% target without meaningful restraint in government-administered prices, the private sector would be forced to bear the full adjustment burden. Specifically, private sector inflation would need to fall to around 2.6% (roughly half its long-term average) to compensate for persistently higher public sector inflation.

Figure 2: Public vs private sector inflation in SA

Source: Codera Analytics

This dynamic starkly highlights the importance of coordination. Without alignment from government-driven cost components, the SARB would be compelled to maintain tighter-for-longer monetary policy, pushing private sector inflation even further below target and weighing disproportionately on output and employment. As such, political coordination is another stumbling block. While the SARB is clearly committed, National Treasury has signalled hesitation, tasking its staff with alternative scenarios rather than aligning with the Bank’s proposal. Treasury fears that a premature move could undermine fiscal planning, particularly since government revenue projections are currently built on 4.5% inflation assumptions. If inflation falls to 3% while spending rises as though it were 4.5%, the fiscal balance could worsen, undermining credibility rather than restoring it.

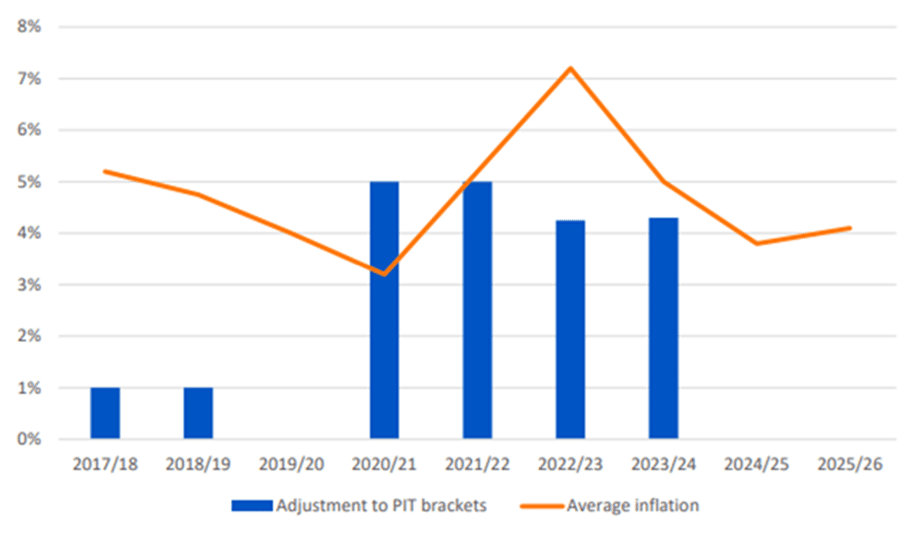

A less often acknowledged reality is that the Treasury has historically relied on inflation to help balance its books. In the latest budget, for example, it expects to raise R15.5bn by once again refraining from adjusting personal income tax brackets for inflation- a move repeated for the second year in a row. Lower inflation erodes the effectiveness of this approach. Asking Treasury to support a 3% target would therefore require downward revisions to both spending growth and revenue projections- an adjustment that will be politically difficult to make.

Figure 3: A growing reliance on bracket creep

Source: BER

The road ahead

The debate thus boils down to timing, coordination, and credibility. On paper, lowering the target is attractive as it would align SA with peers, entrench lower borrowing costs, and ease fiscal pressures over time. However, in practice, the benefits will only materialise if the entire policy apparatus (think National Treasury, Cabinet, state-owned enterprises [SOEs], municipalities, and trade unions) commits to the adjustment. Otherwise, the SARB will be forced to achieve the target by throttling private demand, risking growth at a time when the economy can least afford it. There is also a narrow window of opportunity. Inflation is temporarily low, but it is forecast to rise in the second half of 2025 as food, fuel, and utility costs pick up (see our note entitled: The return of price pressures: Why July’s inflation print matters for the SA economy, dated 20 August 2025). Anchoring expectations at 3% while inflation is still subdued would be far easier than attempting it once inflationary pressures return.

Ultimately, the success of any new target will rest on SA’s capacity to act collectively. Monetary policy alone cannot deliver 3% inflation. It requires a “Team SA” compact: government restraint on administered prices and wages, credible fiscal consolidation, and structural reforms to boost efficiency. Without this, the risk is that the SARB pursues a target that the rest of the government undermines, leaving the economy with higher rates, weaker growth, and no credibility gains.