There are now too many major lawsuits against the US technology (tech) giants to ignore. The US tech industry is facing more and more legal cases that allege Apple, Google, Amazon, and Meta are involved in anti-competitive activities that violate US antitrust statutes. These four companies, together with Microsoft and Nvidia, both subject to prior antitrust cases, represent c. 28% of the S&P 500 Index. The ‘Big 6’ are hugely profitable, with profit margins more than double that of the remaining S&P 500 Index companies (21.6% vs 10.6%, respectively). The P/E multiple of the Big 6 – a rough guide to how these companies are priced – is also higher than the rest of the market. It is important to have some understanding of how these lawsuits may pan out.

US antitrust laws are designed to protect competition. These laws, which some have described as sparse, succinct, and vague, fall under three core provisions – Sections 1 and 2 of the Sherman Act and Section 7 of the Clayton Act. Section 1 of the Sherman Act prohibits contracts ‘in restraint of trade’ which typically harm competition – think ‘cartels, tying arrangements, exclusive dealing’. Section 2 prohibits ‘unilateral anticompetitive conduct by dominant firms’ – think monopolies. Section 7 of the Clayton Act prohibits mergers and acquisitions (M&As) that threaten ‘substantially to lessen competition, or to tend to create a monopoly’. Most of the allegations against the Big 6 relate to Section 2, some refer to Section 1, while the Instagram/WhatsApp suit against Meta also includes Section 7 of the Clayton Act.

As Herbert Hovenkamp, an antitrust expert and professor at Penn Law School, points out, if you try to prove market dominance under Section 2 of the Sherman Act, market power attaches to products, not firms. For example, he notes that Microsoft has market power in PC operating systems of 60%-70%, but its Bing product has a single-digit share of the search market. In the suit against Amazon, another Section 2, he believes it may be difficult, and very costly, to prove market power because Amazon’s e-commerce business sells millions of different products.

Below, we discuss some notable cases against the Big 6 tech firms. Our focus is on those filed in the US by either the Department of Justice (DoJ) or the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), both of which enforce federal antitrust laws. The DoJ has oversight of Apple and Google, while the FTC has oversight of Meta and Amazon. Although the FTC pursued the Activision Blizzard case, the DoJ has traditionally handled cases involving Microsoft. We also refer to regulation in the EU, specifically the recently introduced Digital Markets Act (DMA). We have not discussed lawsuits filed in other jurisdictions.

Apple

Notable cases

- In March 2024, the US DoJ launched a major case against Apple for ‘monopolization or attempted monopolization of smartphone markets in violation of Section 2 of the Sherman Act’. The essence of the case is that through Apple’s actions, consumers are forced to pay more and end up having fewer choices. Apple is alleged to have ‘maintained monopoly power in the smartphone market, not simply by staying ahead of the competition on the merits, but by violating federal antitrust law’. The DoJ says that Apple has a 65% market share of the US smartphone market and 70% of premium smartphones.

Having avoided major antitrust activity for years, Apple has called the lawsuit ‘wrong on the facts and on the law’. The company will likely respond by saying it only has a 20% share of the global smartphone market. It will also say it maintains a walled garden in the Apple ecosystem to improve the customer experience and security of the devices and to protect the privacy of its more than 100mn US users. This argument won out in the 2020 Epic Games case when Epic unsuccessfully sued Apple for operating an alleged illegal monopoly via the App Store.

The initial feedback from legal experts is that although the DoJ has learned valuable lessons from the 2020 Epic Games case, Apple has case law on its side, and the company’s emphasis on the security and privacy benefits of its walled garden may win out. Proving a smartphone monopoly may also be difficult if the judge focuses on the global smartphone market – not just the US.

This lawsuit will take years before reaching court.

In the EU, Apple’s App Store is in the crosshairs of the European Commission and the recently launched DMA. The DMA was introduced to limit the powers of the six largest online platforms (known as ‘gatekeepers’) by opening them up and forcing greater user choice. To comply with the DMA, Apple has already ceded ground by allowing sideloading (where apps are downloaded directly from developer’s websites or competing app stores), albeit at a fee of EUR0.5/download after the first 1mn each year. Developers are unhappy with this. EU regulators are expected to investigate whether Apple has gone far enough in complying with the DMA. The company is attracting far more scrutiny and drawing more outrage than the other gatekeepers in dealing with the DMA. We note that Apple’s App Store is estimated to have generated US$27bn in commissions in 2023. A portion of this revenue is now being threatened.

In March, the EU also fined Apple EUR1.8bn for stifling competition in music streaming.

However, Apple’s biggest immediate risk is the DoJ’s case against Google (see below). Google is estimated to pay Apple c. US$20bn p.a. to be the default search engine on Apple devices, a practice that the DoJ deems anti-competitive. This is roughly 5% of Apple’s revenue. Judgement is expected in the next few months.

Alphabet

Notable cases

The DoJ has launched two major cases against Alphabet’s online advertising arm, Google.

- In October 2020, the DoJ sued Google for ‘unlawfully maintaining monopolies through anti-competitive and exclusionary practices in the search and search advertising markets.’ The essence of this case is that Google has a range of agreements with mobile and PC companies like Apple to be the preset, default general search engine on billions of devices. The DoJ lawsuit, regarded as the most important antitrust action since AT&T in 1974 and Microsoft in 1998, went to trial in late 2023. We expect final arguments in May 2024, after which Judge Amit Mehta, from Washington DC, will rule.

In November 2023, Google’s lawyer ‘visibly cringed’ when one of its testifiers disclosed that Google had paid US$26.3bn in 2021 alone to be the default search engine on various browsers, with US$18bn of this paid to Apple. This represented about one-quarter of Apple’s services revenues in 2021 (5% of total Apple revenues). The press typically assumes the payment to Apple is now c. US$20bn p.a.

Hovenkamp from Penn Law School believes the judge ‘will find a way to condemn the large payments Google makes to Apple and others.’

‘If the payments are eliminated, that means device makers like Apple are going to have to decide what they want to do. One option is they continue right on using Google as a default, except they’re not getting paid for it anymore. Another option is they put in a choice screen, which is what happens in the EU. The third one, which I don’t expect to happen, is that Apple will try to develop its own search engine.’

Whatever the verdict in this case, either Google or the DoJ will appeal it. The appeal process will probably be exhausted by mid-2026.

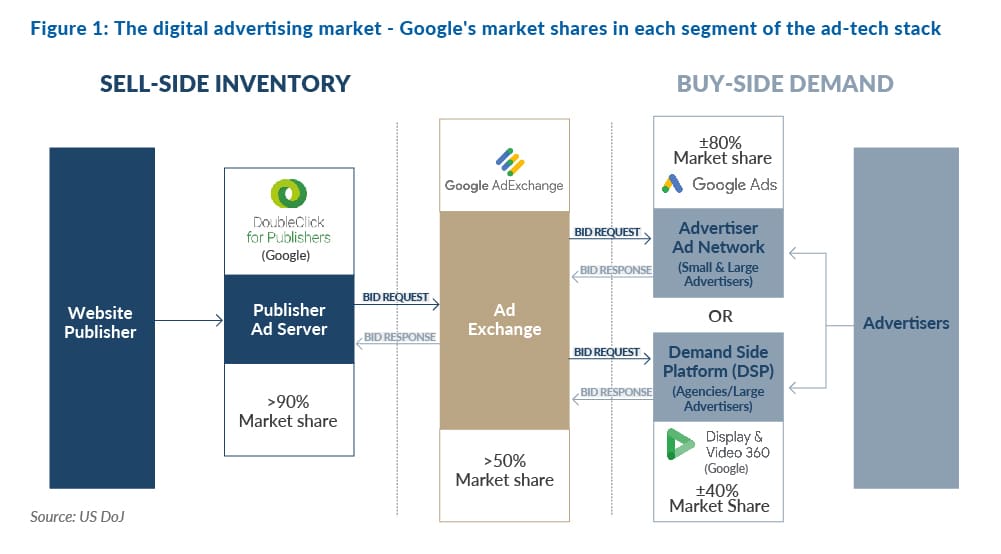

- In January 2023, the DoJ sued Google ‘for monopolizing multiple digital advertising products in violation of section 1 and 2 of the Sherman Act’. This refers to the ad-tech stack that website publishers depend on to sell ads and advertisers rely on to buy ads and reach potential customers. Figure 1 below shows Google’s market shares in each segment of the ad-tech stack. Note that in April 2023, the judge in this case denied Google’s request to dismiss the case.

The DoJ surprised some legal experts by going as far as asking for the unwinding of some prior Google acquisitions like ad-serving Google Ad Manager – formerly DoubleClick – (>90% market share) and called for the divestment of its ad exchange (>=50% market share). In 2022, Google offered to (to avoid this lawsuit) split off some ad tech businesses and place them under the Alphabet umbrella – but the DoJ was not interested. In the final lawsuit, the DoJ included a quote from a Google executive comparing the company’s control over ad tech to the financial sector: ‘The analogy would be if Goldman or Citibank owned the New York Stock Exchange.’

Legal experts believe that Google is vulnerable in this case and may well lose. Its market share is high, and its power over buyers and sellers of advertising in the ad tech stack is unhealthy and ripe for manipulation. Other regulators are also having a look – in the UK and the EU, and in a similar antitrust case in France, Google settled by paying a fine.

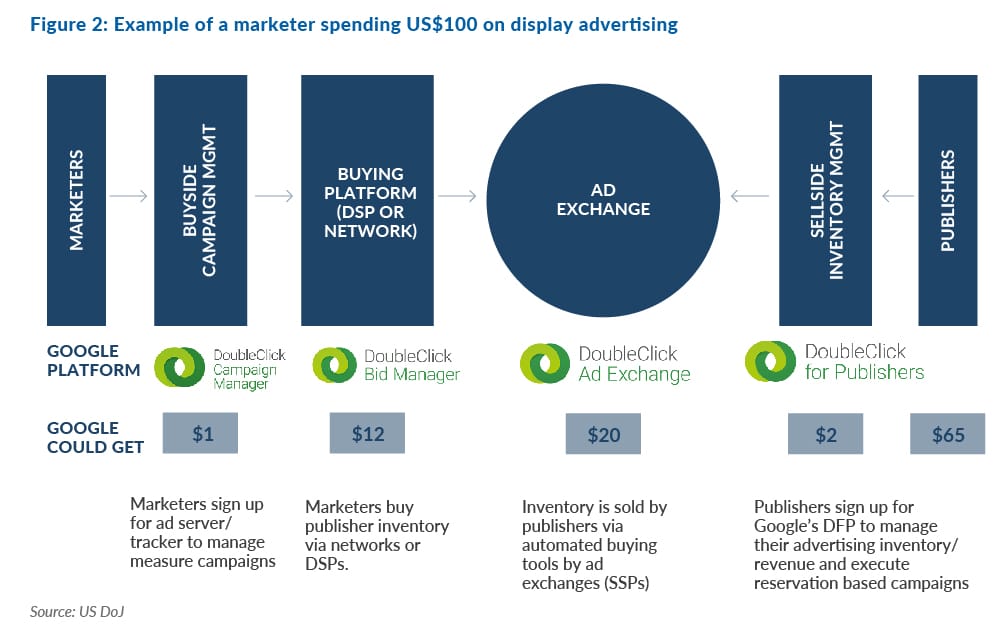

How big is this area for Google? Although advertising accounts for c. 77% of Alphabet’s revenues, this lawsuit only targets a portion of this – ad-brokering activity on third-party websites. This falls under Google Members’ revenue on the income statement, representing US$31.3bn in 2023, or 10.2% of Alphabet (down from 12.3% of revenues in 2021). The DoJ claims Google keeps at least USc30 out of each advertising dollar that flows through this ad tech stack. However, this is at lower margins than the core search business, which means that any changes that are made to Google’s ad tech stack would probably only be a glancing blow to Alphabet.

Amazon

Notable cases

- In September 2023, the FTC sued Amazon, claiming that the online retail and tech company is a monopolist that maintains its monopoly by illegally blocking competition, allowing it to inflate prices, degrade quality, and stifle innovation for consumers and businesses. The case is focused on two parts of Amazon’s online retail business – the online ‘superstore’ and the online marketplace (i.e., first-party retail and third-party marketplace).

One of the juicy revelations in the FTC’s papers was ‘Project Nessie’, where Amazon used an algorithm to increase prices as far as possible, without losing customers, to manipulate the algorithms of other competitors whose pricing strategy is purely to mimic Amazon’s prices. The FTC alleged this practice cost US consumers an extra US$1bn through higher prices. Amazon says Project Nessie was discontinued in 2019.

This case is set to go to trial in October 2026.

Michael Carrier, at the Rutgers Institute for Information Policy and Law, says the case ‘is a bit of an uphill climb. One of the real challenges here is that consumers are happy with Amazon.’ US antitrust doctrine has typically prioritised consumer welfare. Hovenkamp ‘doesn’t see a lot coming out of the Amazon case.’

In this lawsuit, the FTC seeks relief from various anti-competitive practices. It does not call for the company to be broken up.

Meta

Notable cases

- In December 2020, the FTC sued Meta Platforms (then known as Facebook) for accumulating monopoly power via anti-competitive mergers focused on the acquisitions of Instagram and WhatsApp. The FTC seeks to force Meta to divest from Instagram and WhatsApp. The legal action relates to Section 2 of the Sherman Act and Section 7 of the Clayton Act.

After initially being dismissed in June 2021, the lawsuit was refiled, then survived a motion to dismiss, and is still alive. The FTC is pushing for this trial to begin in 2024.

Legal experts believe that if the FTC can prove that Meta has market power in the social media product market, then ‘the case for undoing those two mergers is a good one.’ After all, Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg wrote in an email in 2008 that ‘it is better to buy than compete.’ However, proving market power will be difficult in one of the tech industry’s fastest-moving segments.

Meta notes in its 2023 annual report that it is facing numerous cases in the US related to section 230 of the Communications Decency Act – which protects online platforms from legal liability over content posted by their users. To date, the US Supreme Court has sided with the tech platforms over Section 230, but there is growing pressure for change in a post-truth world.

Microsoft

Notable cases

In January 2022, Microsoft announced a deal to acquire Activision Blizzard (a video game publishing company) for US$68.7bn, the largest deal in tech history. Activision Blizzard is the publisher of Call of Duty. In December 2022, the FTC filed an administrative complaint to block the deal because it would suppress gaming competition. This case was rejected in July 2023, and after a change of heart by the UK regulator, the Capital Markets Authority (CMA), the deal was closed after Microsoft had granted concessions. The FTC is appealing this decision.

This was a win for Microsoft and evidence of its skill at handling regulators. Microsoft had learned valuable lessons the hard way in its historic DoJ antitrust case of the late 1990s when it was found guilty of anti-competitive practices in the internet browser market. The judge ordered Microsoft to be broken up into two units – operating system and other software. Fortunately for Microsoft, this judgement was overturned on appeal.

Nvidia

Notable cases

Although Nvidia, the largest graphics processing unit (GPU) company in the world, is being investigated by antitrust regulators in multiple jurisdictions, there are no notable cases against it.

In December 2021, the FTC sued to block the proposed US$40bn acquisition of chip design provider Arm because the combined firm could stifle competing next-generation technologies. The case was closed in February 2022, when the proposed deal was terminated.

Conclusion

US antitrust enforcement has weakened considerably over recent decades. Some argue that this has led to increased market concentration in various industries. The rise of the tech industry, with the inherent tendency to create monopolies through network effects, has presumably played a major role. In July 2021, the White House issued an executive order on competition policy that signalled a change in direction. The executive order highlighted 72 discrete measures to stamp out anti-competitive practices. Personnel changes at the DoJ and the FTC have reinforced this shift. Although some of the antitrust lawsuits under discussion were launched under the Trump administration, we are only now clearly seeing the consequences. Antitrust is witnessing a rebirth and it appears to have bipartisan support.

This will make life more difficult for the Big 6 tech firms. Even if they prevail in most notable lawsuits, they are already more circumspect about pursuing M&A activity. Antitrust is now a key factor in their acquisition strategies while it used to be an afterthought. If regulators want to pursue an important case with lower odds of success, they are more inclined to file suit than before. As the FTC’s Lina Khan says, ‘You lose all of the shots you don’t take.’ With Congress so fractious and unlikely to pass legislation that would reform aspects of antitrust law, this expensive approach almost makes sense. After all, in antitrust matters, the courts have placed consumer welfare above all else for the past four decades. Maybe it is time for some new legal precedent.

The reality is that Europe, with few of its own major tech platforms, is now the leader in regulating tech. The EU’s DMA, which dictates how the six gatekeepers—Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, ByteDance, Meta, and Microsoft—must compete in the EU, came into full effect in early March 2024. The question now is: Will the EU regulators uphold the law aggressively enough? The gatekeepers are not shrinking violets.

The Big 6 are entering a delicate period of having to navigate both antitrust lawsuits of vital importance and a period of heightened vulnerability as the industry races to roll out generative AI. History tells us that IBM, AT&T, and Microsoft were famously debilitated by antitrust cases that dragged on for years. This crop of firms will have little room for distraction. Ultimately, however, the reason we are here is because the tech sector and the economy need healthier competition.